Although it feels almost sacrilegious, I have recently come around to the linear probability model (LPM). It is easy to understand, its problems are surmountable, and it actually outperforms logistic regression under certain conditions.

As I often point out, I have a soft spot for “ham sandwiches”, which is basically a catch-all term for non-ideal conditions for statistical analysis. Recently, the ham sandwich I was interested in is estimating the relationship between two rare events with a moderate sample size. Coming from criminology and criminal justice, there are many rare but meaningful events worth empirically scrutiny, like…murder! And there are exogenous, rare events or characteristics that truly influence the probability of someone committing murder.

Ok, a bit morbid…

…whether it is murder or seeing a rainbow in a given month of the year (better?), there can be meaningful, rare things that predict other, meaningful and rare things. And in such a situation, particularly without a giant sample size, models often don’t “work” as well as we want them too and inference can be sketchy.

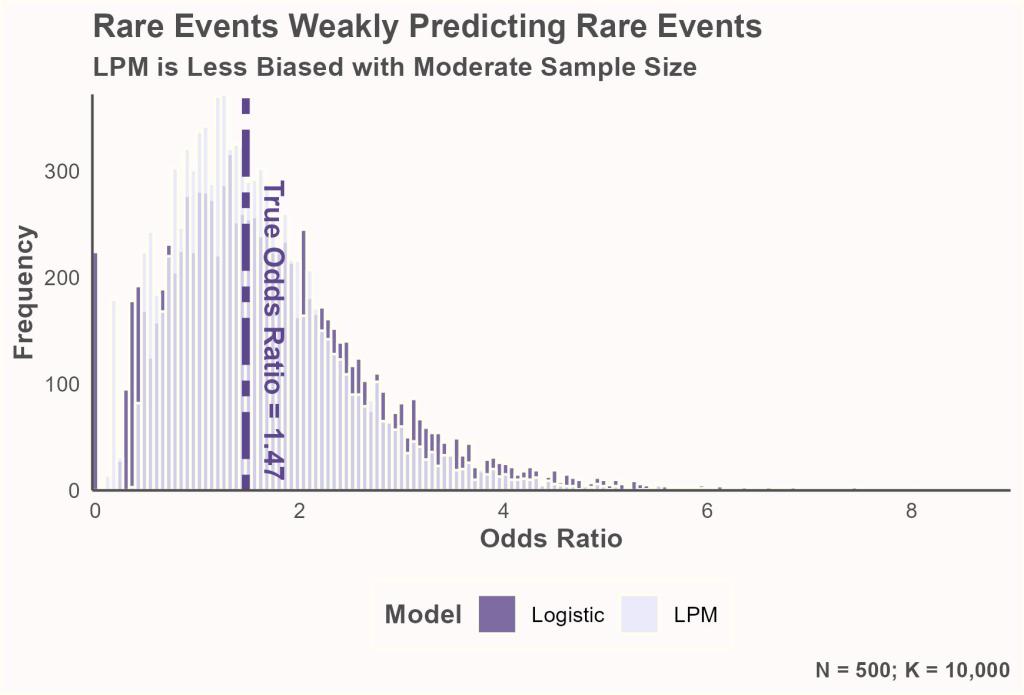

Below is a histogram showing the odds ratios from 10,000 simulations. For the simulations, I modeled the independent variable as a Bernoulli distribution with a probability of .05. For units that were assigned a value of “1”, the dependent variable had a .15 probability of being “1”; for units that were assigned a value of “0”, the dependent variable had a .10 probability of being “1”. For each simulation, I estimated a linear probability model and a logistic regression model; the estimates were saved and transformed into odds ratios. The sample size was always 500.

Whereas the odds ratios from the logistic model were pretty severely, upwardly biased (about 16%), the odds ratios from the linear probability model were not (about 7%). The bias of logistic regression in situations like this is actually well-known (example). However, I had some internal resistance to the linear probability model–a resistance I’ve seen in others too–probably stemming from a formal statistics education that more-or-less glossed over LPM. Even my favorite stats book of all time only briefly presents LPM, mainly as a speed bump on the way to introducing binomial models.

Convention is hard to override. Even the people we attribute convention to lament it:

The emphasis on tests of significance, and the consideration of the results of each experiment in isolation, have had the unfortunate consequence that scientific workers have often regarded the execution of a test of significance on an experiment as the ultimate objective. Results are significant or not significant and that is the end of it.

Fisher thought of things like ANOVA as capitalizing on mathematical properties. Recently, I’ve been trying to adhere to that mindset. On the day-to-day, I think lots of people and organizations want to know if thing A substantively relates to thing B with some degree of certainty. And a bunch of limited studies over time to answer that question will be more valuable than one “gold standard” study sometime in the future. In this case, a bunch of ham sandwich studies using LPM over time would result in an accurate estimate of the odds ratio and allow for a running assessment of certainty.

The two main issues with LPM are: 1) incorrect standard errors, and 2) potential predicted probabilities outside the scale. The former is easy to address with a heteroscedasticity corrected covariance matrix or other method for estimating robust standard errors; the latter can be inspected and weighed against priorities if present. In this scenario, I was focused on accurately estimating relative odds, but that will not be the priority in every case. Although LPM is not the end-all-be-all, I am surprised by how useful and robust it is–and in some cases, it is better than what convention would suggest.

Leave a comment